Serious Games: Imagining Health Futures

Last summer, Jason Morningstar and I co-designed Imagining Health Futures, a game about the future of health and adolescence, in support of UNICEF’s Office of Innovation. Here’s a quick overview of the game and our design choices.

Here are the quick links to the game resources:

The Goal

The high level goal of the game was to better understand the preferences and expectations of today’s youth as it relates to health and wellness now and in the coming decades 2030-2050. Another goal was for the game to produce outputs that might inspire science fiction short stories by professional authors that would further share insights generated during the game.

The Game

The game itself was built to be played with 1-2 facilitators and 3-6 teenagers in ~2 hours over video chat. We broke the game into four stages to ease the participants into playing and to best capture their creative output.

Throughout the game, we have players logging their decisions in a Google Form which enables us to review and share their creative output after the session and allows facilitators to focus on the players rather than on note-taking.

Here’s an overview of the four stages with some commentary on our design decisions.

Stage 1: Worldbuilding

We opened up play with a worldbuilding round which served a few purposes:

- Start aligning on a shared version of the future (in the year 2035), which will be used for the rest of the game

- Start play with low stakes creative decision as the players get to know each other

- Create space for the players to express their interests and preferences around possible trends.

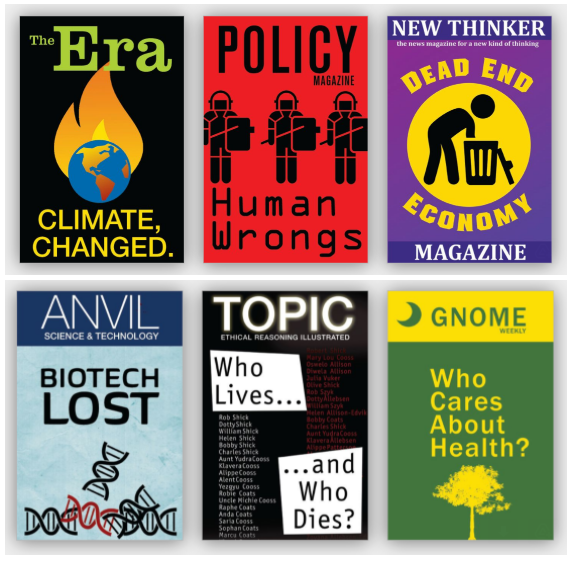

We explored a variety of worldbuilding approaches and knew that we wanted players to engage with different types of trends but especially those related to health. We ended up distilling down possible trends to six, in two groups:

- Non-health trends: climate change, justice and human rights, economy

- Health trends: health technology, health access, and health engagement

We had the players then choose one trend from each group to be clearly negative; these trends would play a key role in influencing the rest of play. We presented the trends to the players via fake magazine covers, which Jason did a phenomenal job designing!

Stage 2: Character Creation

The next stage had players creating characters who were roughly their age, but in 2035. We broke this into two parts: players did some initial creative work on their own and then finished character creation with the whole group.

The character creation process involved players answering a series of questions on their own, including picking an archetype (e.g. activist, academic, joker) and defining how their characters are both similar to and different from themselves. We wanted them to be able to draw on their own experiences but also keep some distance between themselves and their characters.

Once everyone had answered their initial questions, they shared their characters with the group and then each player had to answer one new question about their character. The player always had two questions to choose from, which gave them flexibility in building out their character. The facilitator could then use the player’s answer to create connections with other characters. For instance, if the question was “What volunteer organization are you involved with?” then, after the player answers, the facilitator might ask “Who else is involved with that organization?” which helps tie the characters and setting together.

Stage 3: Storytelling

After the players establish their characters, the players tell stories about they overcome obstacles and engage with their community. This stage of play kicks off with a major crisis upending the characters’ world: a massive malware attack that takes down critical infrastructure and tanks the economy. The players explore this crisis through three rounds which span from the immediate aftermath to the recovery.

Round 1: Initial Obstacles

The first round of storytelling takes place in the days after the malware attack. Each player is assigned an obstacle or dilemma and describes their character’s response. For example:

Water is being rationed after the failure of the city’s air well condensers and desalination plants. You know a local family is cheating the distribution scheme, but you also know they are caring for sick relatives. What do you do?

Players then narrate their characters’ actions to the group.

Round 2: Conversations

The story now jumps forward a month, where critical infrastructure is stable but the broader crisis continues. Players pair up to have in-character conversations about different topics. For example:

With the world suddenly up-ended, many of your character’s friends have been rethinking their longer term plans. Some are devoting themselves to helping in the community and others have seen unexpected opportunities amid the crisis. Have a conversation about what might change about your future plans, and how you will make those changes.

Round 3: Epilogues

The story continues six months after the attack, as a new normal emerges. Players take turns describing what comes next for their characters.

Stage 4: Artifact Creation

The final stage of play has players creating an artifact that captures their characters’ stories from their perspectives. Suggested artifact types include: journal entries (video, audio, or text), letters to the editor, or artwork. Our design goal for these artifacts was that they would capture some of the key facets of the setting, characters, and plot in an easily sharable way.

The framing of the section is that the news media and politicians have gotten the crisis wrong, downplaying the harm and overlooking the hard work done by people in their community.

If there’s time, players then share their artifacts and then the facilitator leads a quick debrief.

Facilitator scaffolding

One of our aims was to make the game easy to facilitate, even for folks unused to these types of games. We used a variety of techniques to support facilitators, including:

- Providing a walkthrough of the game and responsibilities in the facilitator guide, with extra advice and examples

- Including all instructions and prompts in the facilitator slides so that they don’t need to flip back and forth between the slides and the guide

- Creating space to welcome the players and introduce norms and expectations for the session

- Having players capture their activity in a Google Form so that the facilitator doesn’t have to take notes

Beyond that, we designed the sequence of activities to be as smooth as possible by:

- Keeping each activity focused and highly scaffolded with clear instructions and easy individual steps

- Ensuring that the player always has obvious options to fall back on

- Having each activity be a foundation for the next one (worldbuilding -> character -> plot)

- Starting with low-intensity activities (e.g. worldbuilding) and get more intense over the course of play (e.g. roleplaying)

Closing thoughts

Designing a serious game for adolescents to play remotely during a pandemic was an interesting design problem and I’m proud of how the game turned out. I hope you’ve found this overview helpful and I’m excited to reuse many of these design patterns in the future.